As Donald J. Trump attempts to assemble his cabinet, he can only look with envy on George Washington, who could tap such towering figures as Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state and Alexander Hamilton as secretary of the Treasury. Long before the hit musical bearing his name, Hamilton’s greatest achievement may have been putting the young nation’s finances in order with an innovative plan to consolidate its debts going back to the Revolutionary War.

Trump could use a modern Hamilton as he contemplates America’s heavy debt burden and its need for faster economic growth. The federal government today has $14 trillion in debt owed to the public. If the Trump administration were to add no spending programs and cut no taxes, the rising costs of existing programs like Medicare and Medicaid would likely push the national debt to $45 trillion in 20 years’ time. So says the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

The annual interest on a $45 trillion debt load would be about $750 billion at today’s superlow interest rates. If rates rise to a more typical level, the interest on a $45 trillion debt would be about $1.5 trillion a year. That’s right, $1.5 trillion a year in interest payments, as much as the federal government’s total spending over the past five months.

And that’s before President-elect Trump launches his ambitious spending programs and tax cuts, which are expected to add $6 trillion to the national debt over the coming decade. We expect some, but not all, of those proposals will be blocked by the Republican Congress.

Given the incoming administration’s ambitious plans, and the nation’s already high debt, the president-elect might ask: What would Hamilton do?

With long-term interest rates hovering near their lowest levels since the founding of the republic, Hamilton might well answer, Take advantage by issuing Treasury bonds now—and for the longest term possible.

In today’s market, that would mean issuing securities far beyond the Treasury’s current lengthiest maturity of 30 years. Unlike his less-hidebound foreign counterparts, Uncle Sam has been resistant to departing from long-established borrowing habits. Meanwhile, governments such as Ireland, Belgium, and even Mexico have been opportunistic by issuing 100-year bonds.

The reason should be clear from a perusal of the nearby chart showing the history of long-term U.S. interest rates going back to Hamilton’s time. Through a civil war, world wars, and depressions, the cost of borrowing has waxed and waned.

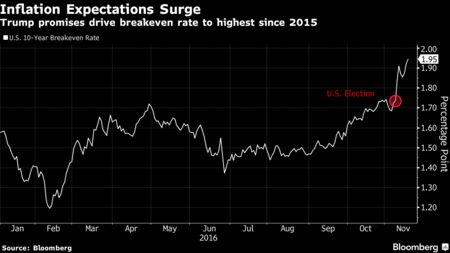

The most recent period has been the most extreme. From a peak of about 14% in 1981, the 30-year Treasury bond’s yield reached a low of 2.09% earlier this year. While the yield has moved back toward 3% with the surge in rates after the U.S. elections, it is still exceptionally low by any criterion.

Viewed against the sweep of history, the graphic shows that interest rates move in long cycles. The great post–World War II rise in bond yields lasted roughly 35 years, until it peaked after a surge of inflation in the 1970s. Since then, rates have been on a 35-year downward swoon.

WHETHER BY HISTORICAL coincidence, a shift in central-bank monetary policies, or the populist wave that has shaped both the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union and Trump’s triumph in the U.S. presidential election, interest rates appear to have hit their trough. That, of course, will be known only in retrospect. What seems certain is that today’s interest rates are far closer to their lows than to their highs.

Given that, the call for borrowers should be clear: Go long. It doesn’t take a genius on the order of Hamilton to realize that. U.S. homeowners have been taking advantage by locking in 30-year fixed-rate mortgages in the 3% range. If they haven’t, it’s because they may have opted for shorter-term loans of about 15 years, probably because they are approaching retirement and prefer to spend their golden years debt-free.

For a nation, however, it’s different. One should match one’s liabilities with the life of one’s assets, says James Bianco, head of Bianco Research and one of the most astute observers of financial matters. Given that the United States of America is 240 years old and has an infinite life expectancy, we hope, issuing 50-year or 100-year bonds makes sense.

It evidently does to any number of other nations, including those whose status is rather less gilt-edged than the U.S. Indeed, three members of the group once derisively known as Piigs have been borrowing for longer periods than the U.S. Treasury at attractive terms. Spain and Italy have issued 50-year bonds this year, while Ireland was able to place a 100-year bond last year. (Of the other members of the group, Portugal hasn’t issued superlong debt, while Greece hardly is in a position to do so, especially while President Barack Obama last week was calling for more debt relief for the beleaguered borrower.)

Belgium was also able to issue a 100-year bond this year, while Austria last month split the difference by going with a 70-year maturity, locking in 1.5% borrowing costs for the proverbial three-score-and-10 life span.

To be sure, these nations have been able to take advantage of the European Central Bank’s effort to stimulate the region’s ailing economies by buying up just about every bond in sight. In the process, yields have fallen, below zero in many cases, leaving long-term investors such as insurance companies scrambling to find investments that pay enough to fund their long-term liabilities.

BUT THOSE INVESTORS need to have the confidence that the nations issuing these bonds will be able to meet their obligations stretching into the next century. Apparently they do, as evidenced by the ability of Mexico to issue 100-year bonds. It should be noted that those securities were denominated not in pesos but in euros.

Some might say it’s a leap of faith that the euro will exist by the time Mexico’s 100-year bonds mature. But the peso looks even shakier.

In 1976, the Mexican currency was fixed at 12.5 to the dollar. By the crisis of the mid-1980s, it took 150 pesos to fetch one greenback. By 1992, it was up to 3,000, at which time the government lopped off three zeroes, making the exchange rate three to the dollar. Early in the current century, the peso remained between 10 and 11. Since Trump’s election, however, it has weakened to 21 to the dollar.

The U.S. doesn’t have that problem. Say what you will about the loss of the purchasing power and status of the dollar over the years—the greenback remains the world’s pre-eminent reserve currency. Even though Standard & Poor’s stripped the U.S. government of its triple-A rating, its rivals, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings, still give Uncle Sam their top grade. And regardless of what S&P thinks, the bond world still accords U.S. Treasury securities an unequaled status, making it easy to issue 100-year bonds in dollars.

So why don’t the nation’s debt managers exploit that to the fullest? James Bianco’s answer is that the Treasury mainly caters to the preferences of Wall Street—both in terms of the big banks that underwrite and deal in its securities as well as the asset managers and hedge funds that invest in and trade them.

The dealers prefer that the Treasury issue securities with maturities of five, 10, and 30 years, which can serve as benchmarks to price corporate and mortgage securities. The 10-year Treasury note is particularly important because a “30 year” mortgage has an actual life span close to a 10-year note. The reason is that a home loan may be paid off early if the borrower wants to refinance, or because life events such as moving, divorce, or death result in the sale of the home.

Cash managers also like having short-term Treasury bills as convenient and safe repositories, especially with money-market-fund reforms that recently took effect. But Bianco says catering to these preferences has produced “the ultimate perversion”—floating-rate Treasury notes.

How, he asks, does issuing billions of dollars of short-term floating-rate notes at near-0% help taxpayers?

“They only have one way to float—higher,” says Bianco. That shifts the interest-rate risk from the fund manager to the taxpayer.

THE TREASURY should do exactly the opposite with rates at historical lows—sell ultralong bonds with maturities of 50 or 100 years, just as sovereign borrowers with lesser status and shorter histories have done. Even if the Treasury had to pay a higher interest rate than the 30-year bond’s 2.58%, the rate would still be roughly half the median long-term borrowing rate through U.S. history.

“It’s an interesting idea,” says Mark J. Grant, chief fixed-income strategist at Hilltop Securities. “If you’re a borrower, do it now,” he adds, while interest rates are historically low and probably headed higher. Meanwhile, institutions that have long-term investing goals would be eager to buy 100-year bonds.

With most forecasts calling for interest rates to begin to climb from their historic lows, now is the time to lock in attractive financing costs. That is especially the case if the new administration is about to embark on a fiscal program that involves a steep rise in borrowing and deep tax cuts.

But the Treasury historically has been resistant to innovations, even when the private sector embraced them—and even when they would save the taxpayers money.

During the 1980s, when real interest rates—that is, after deducting for inflation—were at their peak, the Treasury persisted in issuing long-term fixed-rate bonds. Those bonds were terrific investments for bond buyers, who made a killing as interest rates descended from those peaks. But taxpayers were stuck with paying those fat coupons through the next three decades.

Eventually, Uncle Sam did begin to issue Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, in the late 1990s. As inflation declined over time, the cost of the inflation compensation diminished. Meanwhile, the government resisted the issuance of floating-rate securities even as U.S. homeowners and global corporations opportunistically borrowed at variable rates. Adjustable-rate mortgages offered home buyers a good borrowing option if they weren’t going to stay in a house for decades. Then the market came up with hybrid mortgages, with interest rates that were fixed for a period and then floated. Only when the rates hit rock bottom did the Treasury follow suit and offer floating-rate bonds. Bad timing.

True bond-market veterans may be able to reach deep in their memories for the one time in recent history the Treasury did try something innovative. In 1976, the Treasury offered what looked like an irresistible deal; it announced it would sell 10-year notes at what seemed a huge yield of 8% instead of the rate being set at an auction, as per usual. The department was flooded with orders, including ones from individual investors.

As it turned out, the Treasury was the one that got the good deal. Rates were starting their final ascent during the stagflation of the Jimmy Carter era. Then the 8% notes due in 1986 traded down to a steep discount as yields soared into double digits. It may not have been a coincidence that the Treasury secretary at the time was William E. Simon, who had previously headed the government-bond desk at Salomon Brothers—then the pre-eminent bond dealer.

GIVEN THAT THE ODDS today favor higher rather than lower interest rates, now would be the time to nail down historically low borrowing costs. You would think someone like the billionaire president-elect, who calls himself “the King of Debt,” would want to do what he can to minimize his borrowing costs.