Primary Dealer Designation Loses Its Allure

September 12th, 2016 5:46 amVia Bloomberg :

-

Credit Agricole said to decide against becoming primary dealer

-

Regulation, evolving technology dim lure of once-coveted spot

To see how far the prestige of the U.S. Treasury market’s primary dealers has declined, consider the case of Credit Agricole SA.

For years, France’s third-largest bank courted the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, supplying trade and flows data to demonstrate it was worthy of joining the $13.6 trillion market’s middlemen. The bank also expanded its Treasuries business by adding traders and sales staff and sought out new institutional clients.

By last year, the efforts had brought a primary dealership within reach for a bank that agreed in October to pay $787 million to U.S. regulators to resolve allegations it violated sanctions aimed at Iran and Sudan.

But in the end, even after clearing all those hurdles, the 121-year-old bank concluded that belonging to the bond world’s most elite club — the firms that trade with the Fed and are obligated to bid at U.S. debt auctions — wasn’t worth it. Management alerted staff in May that it wouldn’t pursue the credential, according to people with knowledge of the events who requested anonymity to discuss the process.

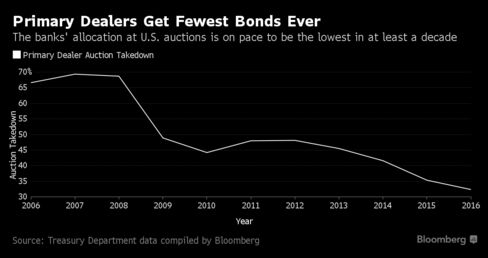

Post-crisis regulation and evolving technology are changing the landscape in the benchmark market for global borrowing. Banks once champed at the bit to become primary dealers. Now the role’s perceived benefits have diminished. Today, a handful of firms dominate trading, and a growing share of auction business bypasses dealers altogether. Last year, 10 percent of new Treasuries went to investors who bid directly with the government, up from about 1 percent in 2006, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“It’s gotten harder for banks to operate a Treasury trading business,” said Kevin McPartland, head of research for market structure and technology at Greenwich Associates, a financial-services consulting firm in Stamford, Connecticut. “Regulation has taken a good amount of profitability out,” he said, not to mention that “as trading becomes more electronic, it’s easier for new participants to enter the business.”

There may be cause for concern if major global banks such as Credit Agricole are losing interest in underwriting U.S. debt. The nation’s borrowing needs are climbing again. Deficits are set to swell amid demands from Social Security and Medicare, and the public debt burden may grow by almost $10 trillion in the next decade, Congressional Budget Office forecasts show.

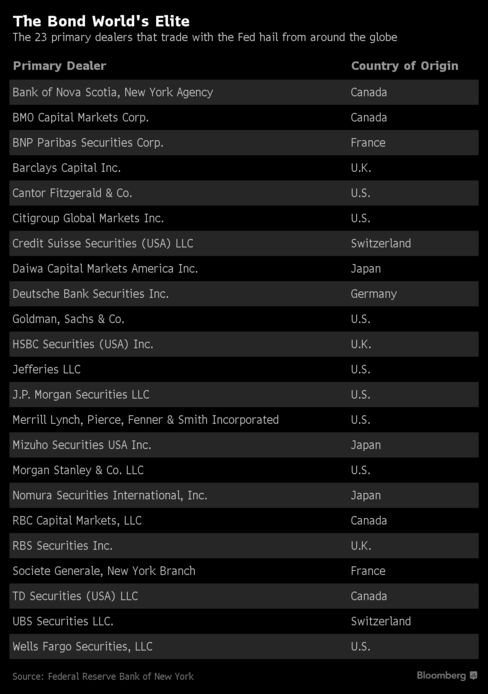

The network of primary dealers has 23 members today, half its 1988 peak. The firms are designated trading partners of the Fed, helping it carry out policy.

The brokerage arm of Wells Fargo & Co. joined the roster in April, the first addition since 2014. Before Wells Fargo, a U.S.-based dealer hadn’t signed on since MF Global Holdings Ltd. in 2011, and that firm was dropped months later after its collapse.

Profit Questions

What was a good fit for San Francisco-based Wells Fargo — the world’s most valuable bank and one of the biggest U.S. mortgage lenders — may have limited appeal for other firms. Some brokerages say the primary-dealer role has become less profitable because rules introduced after the financial crisis, such as Dodd-Frank and Basel III, have made it costly to hold large inventories of Treasuries.

There’s also increased competition from high-speed trading firms on interdealer platforms. Fewer than half of primary dealers in a survey published last year by Greenwich Associates said they’re actively making markets on these platforms anymore. Among primary dealers, Treasuries trading has become concentrated within the top five, which controlled almost 60 percent of volume done by U.S.-based Treasuries investors last quarter, up from 44 percent in 2005.

“For the marginal players it’s not as profitable, so they’re not as active,” said Craig Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston whose research involves risk management. “Those are the ones you’re going to see dropping out, or substantially reducing their participation.”

New Era

Primary dealers are required to bid for at least their pro rata share of the total issuance at Treasury auctions. At one time, the firms went above and beyond this requirement, comprising the largest buyers by far at auctions.

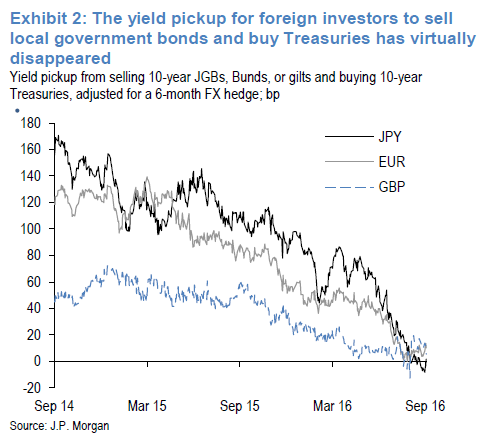

No longer. Dealers have bought about 32 percent of auctions this year, on pace for a record low, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. While that’s partly a result of the rise in direct bidding, dealers have also been left with less to purchase because of the insatiable demand for Treasuries from investors fleeing about $9 trillion of negative-yielding sovereign debt in places like Japan and Europe. The U.S. is selling $44 billion of three- and 10-year notes Monday. Benchmark 10-year Treasuries yielded 1.69 percent as of 10:28 a.m. in London.

“Auctions reveal what is a common theme in today’s market: the diminution of the primary dealer’s influence,” representatives from Daiwa Capital Markets, a primary dealer, wrote in an April response to a Treasury Department request for information about the market’s evolution.

The department’s request is part of the first government review of the Treasuries market since 1998. Industry participants submitted 52 letters, voicing concerns ranging from the unintended consequences of regulation to the need for further oversight. The Treasury and four other regulators also produced a report last year on the state of the market following an unusual bout of bond-market volatility in October 2014.

To read more about the 52 letters, click here.

It’s not just the U.S. that’s dealing with the waning allure of the primary-dealer role.

Japan’s biggest bank, Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd., quit its role as one of that nation’s primary dealers in July. In the U.K., Societe Generale SA resigned its post this year, and last year, Credit Suisse Group AG quit being a primary dealer across Europe, citing the burden of trading under new restrictions.

In the U.S., the qualification process for prospective primary dealers entails financial costs related to maintaining trading capacity and complying with reporting rules. Applicants are required to provide material such as risk-assessment models, internal audits, financial reports and tax returns.

Harboring Doubts

Yet even after jumping through those hoops, and after Credit Agricole management signaled to staff that it was on course to win acceptance, executives doubted the merit of the once-coveted designation, two people with knowledge of the process said.

Mary Guzman, a spokeswoman for Credit Agricole in New York, declined to comment, as did Suzanne Elio at the New York Fed.

At Credit Agricole, which is based near Paris, the decision to forgo a primary dealership dovetailed with plans to slash its debt business, according to three people familiar with the situation. Two of those people said management opted to limit U.S. rates trading mostly to European clients. That meant retreating from the pitch made to new clients in preceding years, when sales staff were encouraged to highlight the pending primary dealer status.

The verdict was in: After a years-long pursuit, the bank was leaving the Fed at the altar.

“The bottom line is there’s a lot more aggravation involved in it than there used to be and a lot less profit,” said Edward Yardeni, president of Yardeni Research Inc. in New York, who’s been analyzing the bond market since the 1970s. “The risk-reward is just not worth it.”