October 7th, 2016 7:25 am

Via Marc Chandler at Brown Brothers Harriman:

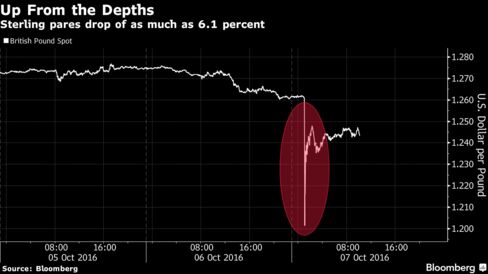

Sterling Stabilizes After Harrowing Drop, Now Jobs

- Sterling again steals the limelight; there are two main schools of thought regarding flash crashes

- German, French, and Spanish industrial output data were consistently stronger than expected

- China is still on holiday, but September reserve figures were reported; Caixin reports services and composite PMI after US markets close tonight

- Attention turns to the US employment data, which will overshadow the Canadian jobs report released at the same time

- Brazil reports September IPCA inflation; Mexico reports September CPI

The dollar is broadly firmer against the majors ahead of the jobs data. The yen is outperforming and up slightly, while sterling is underperforming (-3%) after a -6% flash crash in the Asian session. EM currencies are broadly weaker. IDR and PHP are outperforming while MXN, RUB, and ZAR are underperforming. MSCI Asia Pacific was down 0.2%, as the Nikkei fell 0.2%. MSCI EM is down 0.3%, with Chinese markets still closed for a week-long holiday. Euro Stoxx 600 is down 0.5% near midday, while S&P futures are pointing to a lower open. The 10-year UST yield is up 1 bp at 1.74%. Commodity prices are mixed, with WTI oil down 0.6%, copper down 0.1%, and gold up 0.2%.

Sterling again steals the limelight. In early Asia, sterling inexplicably dropped nearly eight cents in minutes (to ~$1.1840). On some platforms, it may have traded below $1.1380. It almost immediately rebounded but has not resurfaced above $1.2480.

Over the last couple of years, there have been a number of sudden dramatic moves in the foreign exchange market. They have involved currencies like the New Zealand dollar and South African rand. However, major currencies, like the Swiss franc, have also seen dramatic moves, though there was a clear fundamental trigger. The yen has often been subject to sharp moves. And now sterling.

There are two main schools of thought. The first looks at the micro-market structure. The fragmentation, which is partly made possible by technological advances, changes the liquidity distribution. There is the rise of the algo, machine-based trading. There has been a reduction of risk-taking (proprietary trading) at banks. The market is more exposed to short-term leveraged operators, often using reverse knockouts/ins, and one-touch options, which are force multipliers.

The other approach looks at macro-developments. The price of reducing overall volatility in the capital markets is occasional and self-reinforcing spikes. Perhaps it is like a summer storm. The storm itself is partly a function of the previous calm.

Remember the neoliberal argument. If the price of capital is allowed to move, it can act as shock absorber. It can make the adjustment so the real economy (employment, output), doesn’t have to adjust so much. Capital markets volatility is low. Some say it is a function of market direction, which itself is underwritten by the orthodox and unorthodox monetary policy measures. The economic activity appears to have gotten more volatile.

No news is able to rival the dramatic move in sterling today. However, it is notable that the German, French, and Spanish industrial output data were consistently stronger than expected. After reporting a jump in industrial orders to five-month highs yesterday, Germany reported a 2.5% rise in industrial production, more than twice what the median had forecast. It follows a 1.5% decline in July. Manufacturing output rose 3.3%, while energy production rose 1.1%. Construction fell 1.2%.

French industrial output rose 2.1% in August, more than three times the median forecast. It more than offsets the 0.5% (initially 0.6%) fall in July. Manufacturing output jumped 2.2%. The Bloomberg median was for a 0.3% increase. The data stands in stark contrast with the manufacturing PMI, which has been below 50 since March and fell to 48.3 in August from 48.6 in July.

Spanish industrial output rose 1.4% in August. Economists had expected a small decline, though the July series was revised to 0.1% from 0.2%. Italy will report next on Monday. In the middle of next week, the aggregate Eurozone figures will be published. There are upside risks to the previous median forecast of a 0.7% increase.

There were two reports in Asia to which we draw your attention. First, Japan reported labor cash earnings fell 0.1% year-over-year in August. This is down from 1.4% in July. Real cash earnings (adjusted for inflation) slowed to 0.5% from 2.0%. The combination of low wage growth and low interest rates may exacerbate the propensity to save (one expression of which is a larger current account surplus).

Second, although Chinese markets are still closed for the national holiday, September reserve figures were reported. They fell to $3.166 trillion from $3.185 trillion. This is a new five-year low. This was a somewhat larger drawdown than surveys anticipated.

Caixin reports China services and composite PMI after US markets close tonight. Next week, the data deluge for September will be seen, with trade, money and loan data, CPI, and PPI all reported. Off-shore CNH has weakened during this holiday week, and so we expect on-shore CNY to play catch-up.

Attention turns to the US employment data, which will overshadow the Canadian jobs report released at the same time. Outside of the ADP data, other pieces of data pertaining to the US employment were favorable. The one cautionary note is that in recent years, the market has consistently over-estimated job growth in September. The surveys suggest the median guess is around 170k, but we suspect it has crept higher. Other details from the report will also be important, like hourly earnings and average hours worked.

A significant challenge is perhaps globalization. Perhaps the challenge is technology. Those with a college degree have a 2.5% unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is more than twice as high for high school graduates. The unemployment rate for those without high school is almost the sum of the other two (~7.5%). That education/economic dynamic has become a political force to be reckoned.

The short-term market is going into the US report having extended the dollar’s gains, with the US 2-year note yield near four-month highs. The US 2-year premium over EMU and the UK is the most in a decade. The CME model, based on the futures prices, estimates a 55.1% chance of a December hike and a 14.5% chance of a November move. Bloomberg puts the odds at 51.3% and 23.6% respectively.

Between tradition and the lack of updated forecasts, we think the bar to a November hike is very high. Even if our suspicions that the US delivers a robust jobs report are accurate, there are still two other jobs reports that Fed officials will see before the December meeting. There is clearly scope for the market to price in a greater chance of a rate hike before the end of the year. The issue is whether it does so today. In our recent commentary in the emerging markets as well as out profiles of major countries (EMU, Japan, Canada, Norway and Sweden), we have shown how interest rates appear to be re-emerging as an important driver.

Brazil reports September IPCA inflation, which is expected to rise 8.6% y/y vs. 8.97% in August. The central bank has been on hold at 14.25% since the last 50 bp hike back in July 2015. COPOM next meets October 19. It is widely expected to start the easing cycle then, but we it will depend on significant progress in passing fiscal reforms.

Mexico reports September CPI, which is expected to rise 2.91% y/y vs. 2.73% in August. This would still be below the 2-4% target range but it has been rising. Banco de Mexico last hiked 50 bp to 4.75% in September. The next policy meeting is November 17, and much will depend on how the peso is trading. The economy remains sluggish, but the central bank is mostly concerned with the inflation pass-through from the currency. Our base case is steady Mexico rates in November, followed by a hike to match the US if the Fed hikes in December.

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Off on More FX